Data Insights & Analytics, Safety

Samsara Data Shows Risky Driving Behavior Peaks at Start and End of Drivers’ Shifts

August 6, 2020

Driver safety is more important than ever. Although the nation’s roadways may be emptier due to COVID-19, multiple reports have shown that they are not necessarily safer—and may even be more dangerous. In fact, a recent Samsara analysis found that less congested roads have resulted in a 20% increase in severe speeding among U.S. commercial drivers.

To help fleet managers better understand patterns in risky driving behavior, we wanted to know: how does driver behavior change over the course of a shift? When are drivers most likely to exhibit risky behaviors? And how can fleet managers use this data to coach drivers more effectively?

We took a sample of some of our most frequently observed unsafe driving behaviors—including two measured by g-force (harsh acceleration and harsh braking) and two detected using artificial intelligence (distracted driving and tailgating). The sample we analyzed contained more than 2 million of these high-risk behaviors that have occurred across our U.S. commercial fleet customers since January 1, 2020. In order to understand unsafe driving patterns, we looked at the frequency of incidents over the course of a driver’s shift (for more details on how we defined shifts and other technical considerations, see our <a href="#methodology">methodology</a> below). Here are our key findings:

Harsh acceleration, harsh braking, distracted driving, and tailgating occur more frequently at the beginning and end of drivers’ shifts. We found that these risky driving behaviors are 26% more likely to occur in the first tenth of a shift than the middle of the shift. In the last tenth of a shift, they are 41% more likely to occur.

<a href="#section-1">Read more below.</a>There is no one factor responsible for this trend. Our data shows there could be multiple factors leading to these risky driving behaviors, including increased traffic and distractions in cities, last mile stops, and driver fatigue.

<a href="#section-2">Read more below.</a>It’s possible to adjust this behavior. Our data shows that when drivers receive in-cab alerts for harsh braking and harsh acceleration, the frequency of those behaviors is reduced by up to 40%.

<a href="#section-3">Read more below.</a>

Keep reading to learn more about our findings, implications for safety management, and tips for keeping your drivers safe.

Risky driving behaviors occur more frequently at the beginning and end of drivers’ shifts

When it comes to driver safety, there are certain patterns that are widely known. For example, the National Safety Council has found it’s more dangerous to drive at night. And according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, nearly 70% of all collisions in the U.S. occur within 10 miles of the driver’s home. But many commercial drivers work longer hours (and drive farther distances) than the average American driver. How does this affect their behavior?

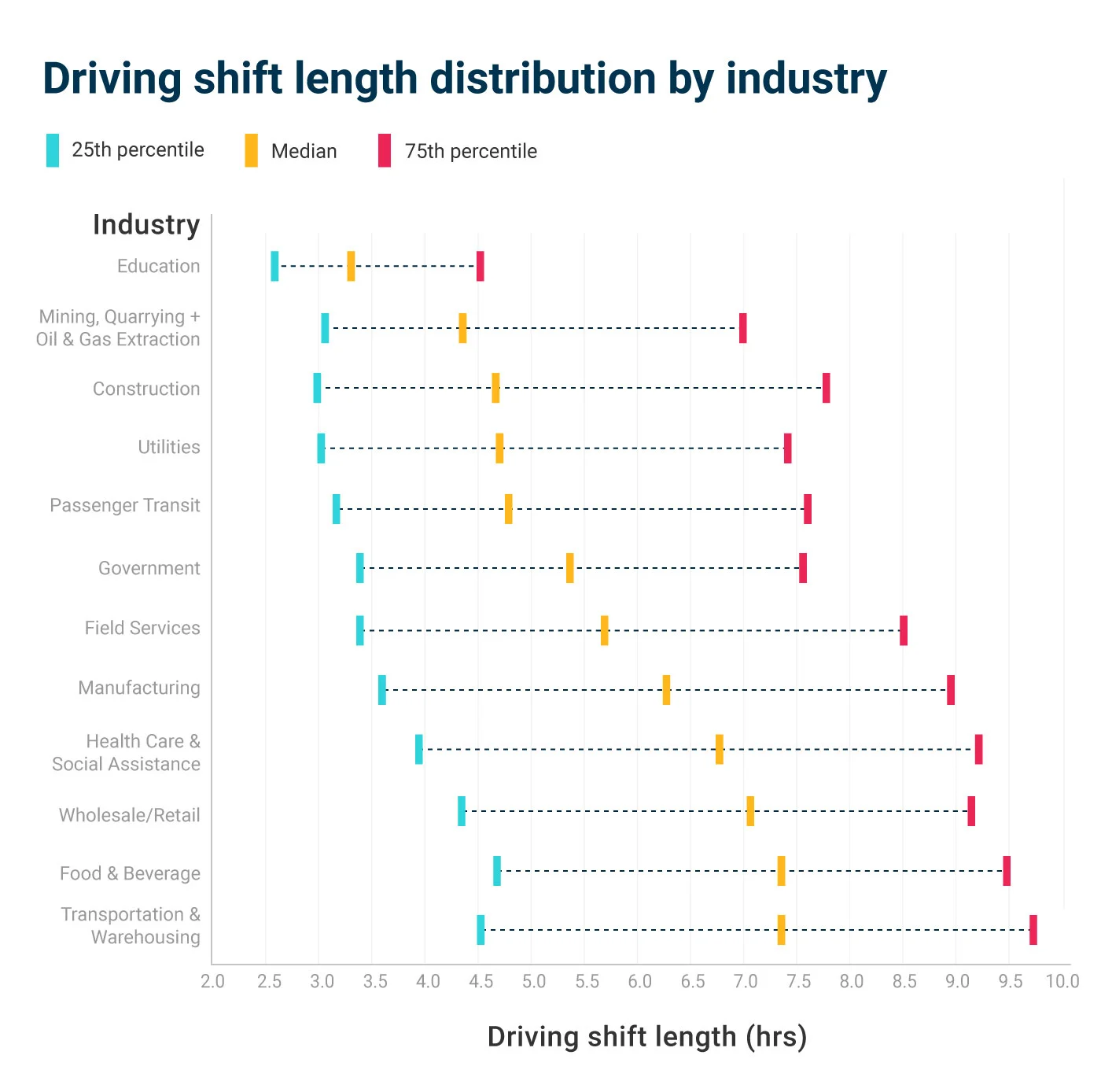

To answer this question, we analyzed driver shifts across the Samsara platform since January 2020. According to our dataset, the average shift length is around seven hours, with some meaningful variations by industry. For example, drivers operating in the transportation and warehousing, food and beverage, and wholesale retail industries tend to have the longest shifts (exceeding seven hours), while those in the education, oil and gas, and utilities industries have shorter shifts (closer to four to six hours).

Despite the variation in shift length, our data shows a consistent trend across shifts. When we looked at our sample of common unsafe driving behaviors, we found that they occur more frequently at the beginning and end of drivers’ shifts.

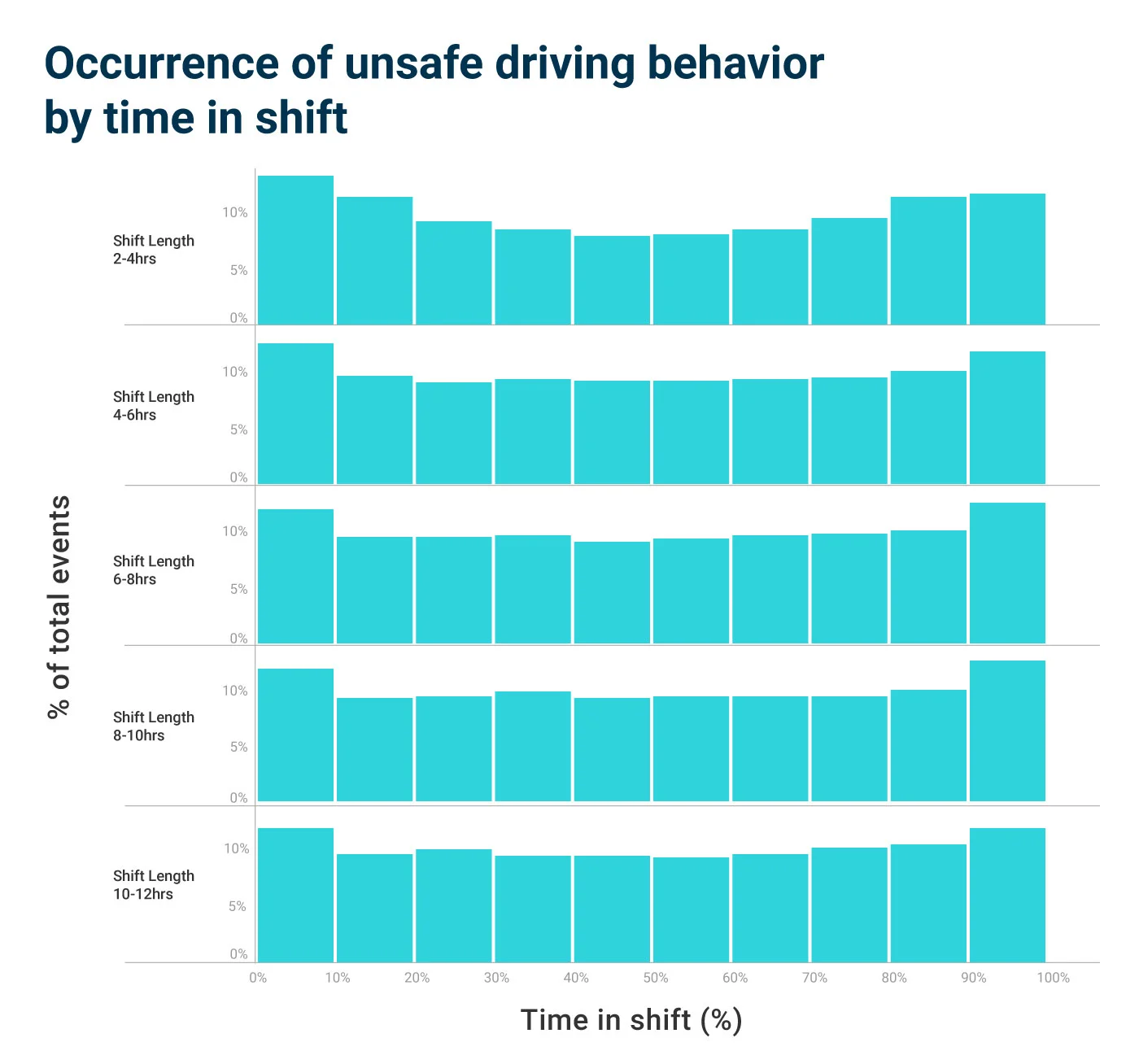

Harsh acceleration, harsh braking, distracted driving, and tailgating are 26% more likely to occur in the first tenth of a shift than the middle of the shift. In the last tenth of a shift, they are 41% times more likely to occur. Our data shows this trend begins to appear when shifts reach about two hours and remains consistent for shifts that are as long as 12 hours. As shown in the chart below, whether you look at a two hour shift or a 10 hour shift, most of these unsafe driving behaviors occur at the beginning and the end of the shift.

Below is a breakdown of frequency by type of risky driving behavior. Harsh acceleration, for example, is an astounding 77% more likely to occur in the last tenth of a shift than anywhere in the middle. Tailgating, which is typically observed in highway driving settings (likely in the middle portion of a shift), is less susceptible to this effect. Still, tailgating behavior is 16% more likely to occur in the last tenth of a shift versus the middle.

There is no one factor responsible for this trend

What’s causing these risky driving behaviors to peak at the beginning and end of drivers’ shifts? There could be multiple causes, including:

Increased traffic in cities: In instances where shifts start on local roads and then move to highways, there could be more traffic and distractions at the beginning and end of a shift.

Last mile stops: Our data shows there are more short trips (likely due to deliveries and last mile stops) at the beginning and end of shifts, causing drivers to stop and start more frequently, which can create more opportunities for unsafe driving behavior.

Driver fatigue: Drivers may be distracted or less alert at the beginning or end of shifts, especially when they are tired.

When we control for each of these factors, we see a reduced effect—but we don’t see the trend go away. This leads us to believe that each of these factors, and potentially others, contribute to the overall trend.

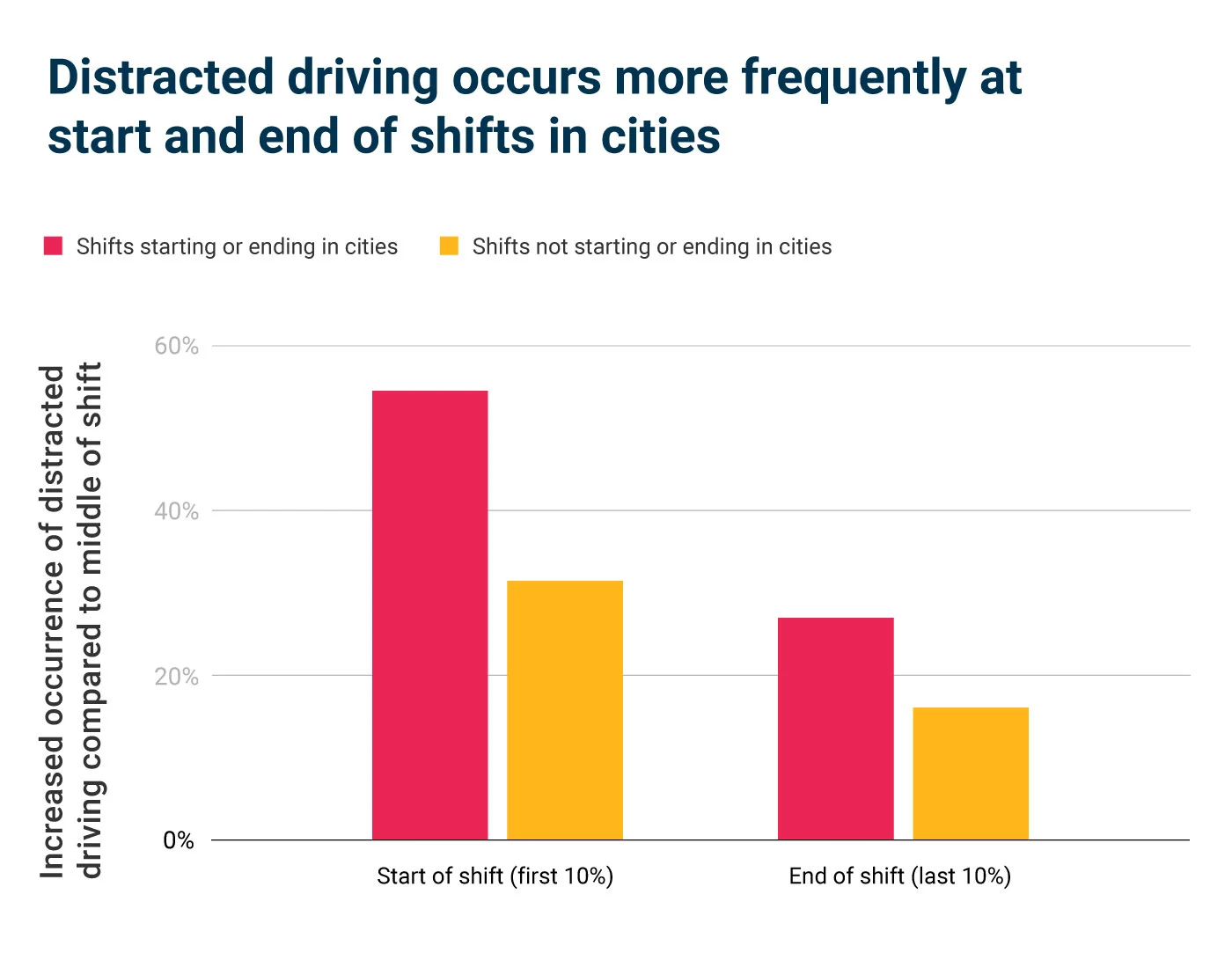

For example, to test how cities could affect this trend, we isolated shifts that started or ended in top 40 U.S. cities and compared them to shifts that did not. Distracted driving was 26% more likely to occur near the end of a shift when that shift ended in a city vs. 17% when it did not—a significant change, but not enough to fully explain the effect.

In addition to cities and last mile stops, driver fatigue may also intuitively appear to be a factor in this trend. According to the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, driver fatigue is a factor in roughly 13% of large truck accidents in the U.S. each year. While we didn't control for driver fatigue in this analysis, we found that the trend persists in shorter shifts (two to four hours in length), when drivers are less likely to be fatigued.

This leads us to believe that cities, last mile stops and deliveries, and driver fatigue all play a role in risky driving behavior peaking at the beginning and end of shifts—with no one factor being solely responsible.

Tips to keep your drivers safe

How can fleet managers put this data into action? Here are a few ways our customers are helping drivers reduce risk while on the road:

Give drivers real-time feedback. Immediate feedback can help drivers adjust their behavior and reduce risk in real time. If you have dash cams with optional in-cab alerts, try turning them on. Our data shows that in-cab alerts related to harsh braking and harsh acceleration can reduce frequency of those behaviors by up to 40%, and we expect this trend to persist for other types of in-cab alerts as well.

Share these statistics with safety supervisors and drivers. Simply being aware of these trends can go a long way towards correcting unsafe driving behaviors. Consider sharing these findings in your next safety meeting or company newsletter.

Include real footage in your coaching sessions. Research has shown that people are 22 times more likely to remember a fact when it is part of a story—and real dash cam footage is a powerful storytelling tool. If you have an example of harsh braking or distracted driving, share the footage with your drivers during coaching sessions. This is often more memorable and effective than coaching with a generic training video. Make sure to share footage of positive driving examples, too. According to a Globoforce, 79% of employees work harder when they feel recognized.

Subscribe to Samsara Data Insights

Want more insights like this from Samsara? Get access to transportation trends as soon as they're released by subscribing to Samsara Data Insights.

Samsara collects more than 1.6 trillion sensor data points yearly from more than 15,000 customers across diverse industries—including transportation and logistics, construction, local government, and more. Our data science team analyzes this data to find insights you can use within your own fleet.

Subscribe now to get the latest insights delivered straight to your inbox.

Methodology

We analyzed Samsara driving data since January 1, 2020 and grouped all trips that occurred for the same vehicle in a continuous time window up to 12 hours long into a single shift. To validate this approach, we also constructed a smaller but statistically significant sample where individual drivers were assigned to shifts by our customers. The same trends were observed in both samples.

We joined the trips data above with our safety events database for four of our safety events: harsh acceleration, harsh braking, distracted driving, and tailgating. Data was joined by vehicle based on whether a safety event occurred in the same time window as a shift.

To calculate the frequency of safety behaviors over the course of a shift, we divided the shifts into buckets of 10% (i.e., first decile, second decile, etc). We averaged the occurrence of safety events in the middle eight buckets and compared this to the first and last decile bucket to get the relative occurrence of harsh events occurring at the start and end of a shift.

We controlled for noise in the data by removing safety events occurring at very low speeds and false positives as flagged by customers or our algorithms to filter out noise.

To control for the effect of shifts starting or ending in cities, we used the Census Bureau’s cities dataset to identify the top 40 U.S. cities by population. We then created another sample excluding shifts starting or ending in these cities and compared the relative occurrence of events for this sample vs. the overall population.